One of the key features of the feminisation of Britain, has been the widening gap between boys and girls in education, with boys falling further behind.

The effect of this feminisation has meant that whereas the previous situation where boys out-performed girls is now reversed, except with one key difference : the relative paucity of action by the authorities and the ‘Equal’ Opportunities movement.

From the seventies onwards, the feminist movement lobbied the Department of Education about the unfair situation where boys got better exam results and more went to university, than girls. This led to the ultimate success of the switch from O-levels to GCSEs in 1988. GCSEs are module/course-work based rather than O-levels which were awarded by competitive exam. This rapidly overturned the gender split and the gap continues to grow with boys’ results now seven years behind those of girls. The Daily Telegraph reviewed this and ran an on-line blog (link)

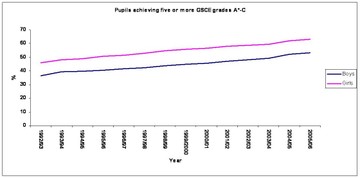

In 2005/06, 53.3% of boys achieved five GCSE passes with A*-C grades, the same pass rate for girls was achieved in 1998/99 (54.4%).

At A-level, girls’ results overtook boys at A-Level in 1998, having trailed behind boys since A-Levels began in 1951. By 2005, the percentages of boy achieving results A-C were 65.5% as opposed to girls 71.9%. In addition, 43% of girls have A-levels or equivalent as opposed to 34% of boys when in 1993, the percentages were 20% to 18% respectively.

Lastly, 2005 figures show more girls go to university than boys now, 47% of girls go against 37% of boys.

There is a growing concern and commentary about the problem. The organisation Parity (link) have organised a conference in April 2007  , the media regularly comment on the gap (link)and Ofsted, the independent inspectorate, are also concerned (link).

, the media regularly comment on the gap (link)and Ofsted, the independent inspectorate, are also concerned (link).

There has been much comment about the difference but little practical achievement and with this government being the most politically correct in British history, there is an absence of fundamental initiatives, just headline grabbing soundbites.

Some of the academics talks about laddishness but boys have always been laddish. Some talk about parents and that girls start school academically ahead of boys, but it is widely known that younger girls develop quicker than boys. Others, talk about the fact that with more opportunities rightly available for women, they are simply more driven in wanting these opportunities and this is pushing them towards better exam results.

None of this is convincing, because it is not enough to explain this absolute fundamental change in education achievement.

The essential issue is that boys and girls are different.

Boys are more competitive, non-conformist, enjoy risk, look at the bigger picture, factual and have shorter attentions spans. Women are less competitive, have more attention to detail, are conformist, more organised with longer attention spans and are more reflective. This has been well researched in an excellent paper by Richard Fisher (link) on the underachievement of boys in writing. Boys write about action, girls write about emotion. Another article by Dr Terence Kealey in The Times also is of interest (link).

IQ tests show that boys do better than girls on numbers, patterns and theories whilst girls are better with language and logic.

The entrenchement of femininity in primary and nursery schools is a concern with over 80% of nursery and primary teachers were women and so, right from the start, boys have few male role models.

The view here is that the switch from competitive exams to module based coursework throughout the examination process (two years for GCSE) has had a bigger impact. They play towards girls’ strengths and not to boys’ strengths and this was recognised by Chris Woodhead, former chief of Ofsted. A paper from the Dr. Madsen Pirie of the Adam Smith Institute fully explains the issue (link).

Due to the one-size-fits-all nature of the government, the British state and the Department of Education’s lumpen antipathy towards real choice, the debate has often been between either O-levels or GSCEs. The solution should be the re-introduction of O-Levels and retaining GSCEs, thereby creating a situation where neither gender are hindered. Labour have talked about it but is it just talk?(link)

Ofsted, recently issued a paper 2020 vision (link) that centred on the need to personalise education to the needs of the individual. Whilst the paper centred its thinking at the school micro-level, if personalising education is to be taken seriously there has to be some macro-structural changes.

If O-levels were re-introduced, the parents of boys and girls would have the choice to choose whatever system played to the strengths of their individual children. The O-levels would have to have the same degree of rigour as GCSEs and schools and local education authorities would be able to offer the choice either at the same school or at different schools. School A could offer GCSEs and school B could offer O-Levels.

This not only would introduce genuine choice but would acknowledge that boys and girls are different and need a different examination system to bring the best out of them. Girls would of course have the same choice as some may be better suited to O-levels, not all girls are the same.

The current government are in hock to the politically correct ideology that all women are victims and all men are oppressors so whilst they talk about dealing with the problem and choice, they offer nothing practically. The EOC ignore the problem altogether for the same reasons (see footnote). If the government changes and with the current fundamental policy reviews by the Conservatives, these changes could and must take place.

Footnote I was informed that at a meeting at the Conservative party conference in 2006, the EOC were lauding about how great it was that girls were outperforming boys and when asked what they were doing to support the inequality for boys, all they could refer to was the Gender Equality Duty. It means, the EOC are not doing anything, because, of course, its more interested in women than men or of course pursuing real equal opportunity.

Comments